by admin | Nov 11, 2022 | Oskar Beck EN, World Cup

When you congratulate a dead person on his 100th birthday, there must be great reasons. Like with Fritz Walter. Only one thing is sad: as a child, I tried, unsuccessfully, to break his 32-stroke record on the mini-golf course in Obertal in the Black Forest.

Every year, just before the holiday season, a colourful brochure from the Belvedere Hotel flutters into my letterbox. In the past, it was delivered by the postman. Today it arrives by e-mail.

Have you ever been to the “Belvedere”?

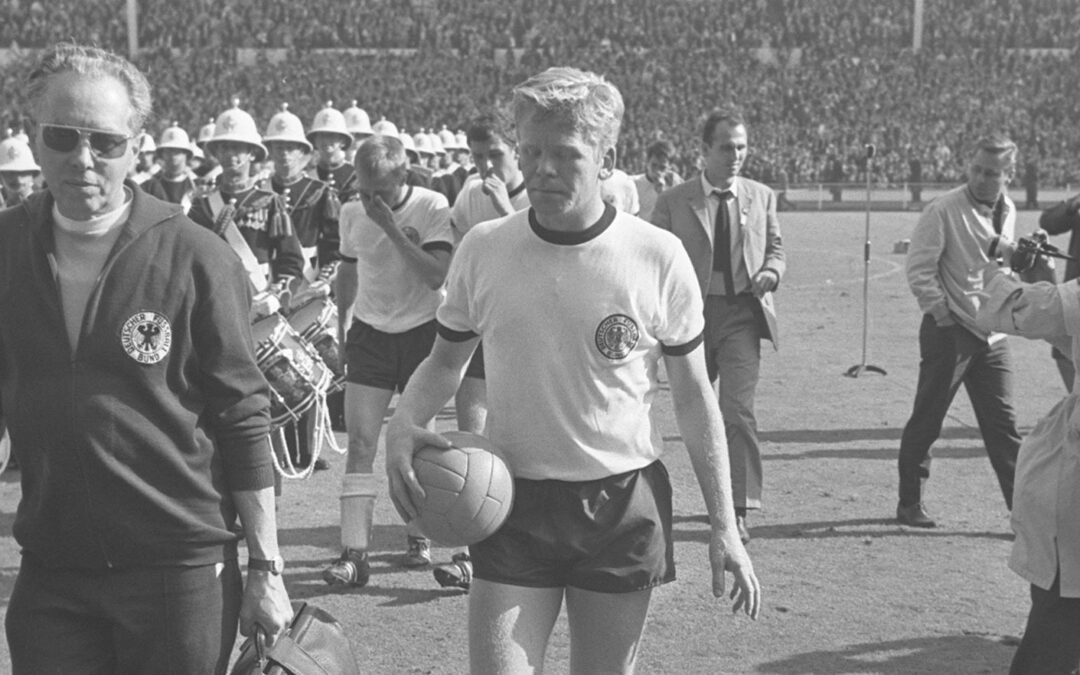

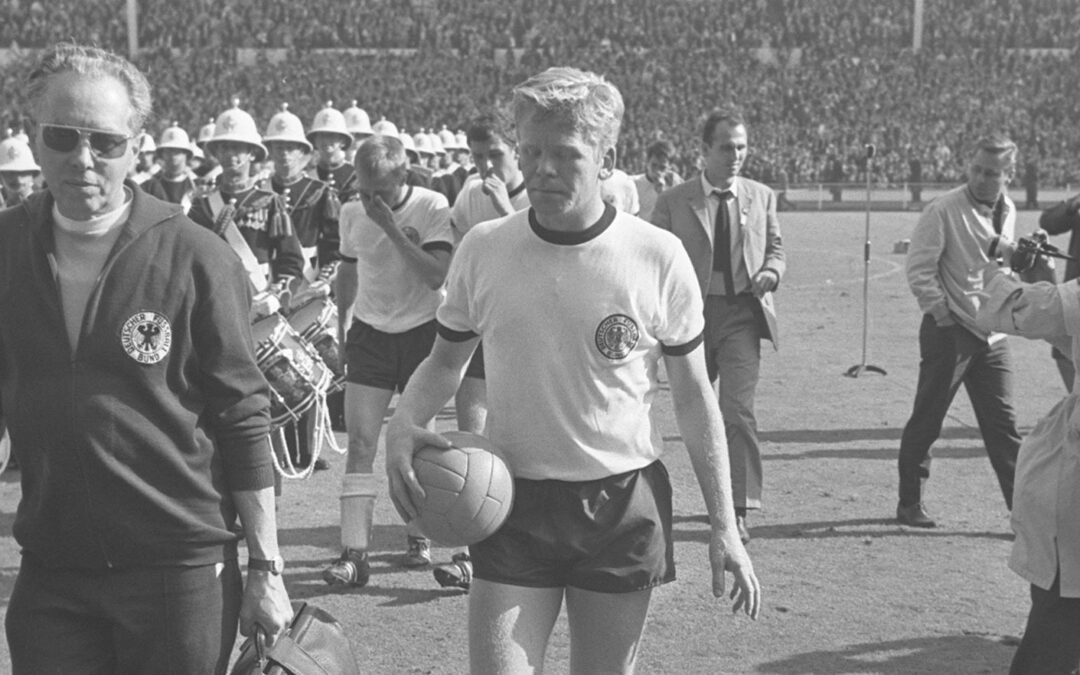

The hotel in Spiez on Lake Thun has been a place of pilgrimage since 1954. Every self-respecting German should visit it at least once in his life and kneel before the steps at the entrance, and when I spent a night there a few years ago, Fritz Walter’s shirt was still available in the fan shop. “From the original jersey,” the hotel guaranteed, “the pattern was taken.”

At the time, however, I had not travelled all the way to Switzerland to buy the old hero’s imitation shirt; rather, I wanted to breathe the unadulterated breath of the heroic deed in the place where the captain Walter and the right-winger Rahn, in short: the “Boss”, had stood in front of the mirror and shaved every morning back then. So I asked the friendly lady at reception, “Can I have room 303?”

She was inconsolable as she revealed to me the bitter truth: “We have remodelled.”

Room 303, the base camp of wonder, was no more. All the more, however, and this halfway saved my day, I could still make out the outlines of the historic dining room where probably the most important three words of German football were spoken on 4 July 1954 – the DFB kickers were sitting at lunch when Max Morlock from Nuremberg suddenly stared through the window and cried out as if electrified.

“Friedrich, it’s raining!”

Friedrich, that was Fritz Walter. “We were gnawing the bones off our chicken at the table,” the captain later described the moment of happiness. He liked damp grass, and his ball skills came into their own perfectly on slippery surfaces. National coach Sepp Herberger also winked: “Fritz, your weather.”

It was weather to produce heroes. And we Germans desperately needed new heroes. The old ones were dead.

The rest of the day is history, the images of the miracle are indelibly stored is all survivors. Boss Rahn’s 3:2. The soaking wet Hungarians. The damp and happy German supporters in their mackintoshes. Herbert Zimmermann’s voice, which increasingly rolled over as he shouted through his radio microphone back home: “Off! Off! The game is over! Germany is world champion!”

4 July 1954 is considered the true birth of the Federal Republic of Germany. “We are who again!”, felt a united people. Overnight, the battered German soul dared to walk upright again – and the German man reached for curling iron and pomade to come across as brilliant as Fritz Walter.

He was no ordinary man. When you congratulate a dead man on his centenary, as you are doing now to this Palatine, there must be serious reasons.

Where do we start?

The best place to start is with his goal of the century. On 6 October 1956, 1. FC Kaiserlautern played against Wismut Karl-Marx-Stadt in front of 110,000 spectators in Leipzig, won 5:3, and Fritz Walter gave the GDR champions the golden shot. In his book “So habe ich’s gemacht …” (That’s how I did it …) he describes it like this: “The cross ball coming from the right sank behind my back. Then I dropped forward, almost in a handstand, and hit it with my heel. From a distance of twelve or fifteen metres, the ball flew into the top corner of the goal. I was lucky that it was a goal. But the fact that I got to the ball at all in that situation and hit it, that wasn’t luck.”

It was skill. He was a gentle stroker of the ball, and old writings describe him as a brilliant playmaker and strategist who defended and executed on the side. In 61 international matches, Fritz Walter scored 33 goals. But virtually none of them came live and in full on television, and certainly not in colour, the pictures were just learning to walk. How good was Fritz Walter? It’s like Muhammad Ali, whose coach Angelo Dundee said, “We never saw the best Ali.” That’s because in his prime Ali was banned as a conscientious objector.

Young Walter went off to war and lost his best days at the front. In 1940, the Reich coach Herberger had nominated him for the first time, he was 19, today one would say wunderkind, and against Romania he scored three goals at the first attempt. Then in 1945 he returned home from Russian captivity, in 1951 he returned to the national team, and he said: “The war stole my best years.” He was past 30. Actually, it was all over. But it was just beginning.

The second life.

Walter no longer played for Hitler, but still for Herberger. The two were like father and extended arm, the filigree implemented the coach’s ideas, and conversely, Herberger was his best man when he walked the good-looking Italia Bortoluzzi down the aisle in 1948. The Palatinate people whispered worriedly in view of the fiery Italian: “The black witch with the red fingernails, I hope she doesn’t finish off Fritz.” In truth, she really got him going. Twice Kaiserslautern became German champions, and Atlético Madrid and Inter Milan lured him with money bags. Unsuccessfully. “Dehäm is dehäm”, Fritz is supposed to have said.

Then came the 1954 World Cup.

The miracle is always explained with the “spirit of Spiez”, but the spirit of the Black Forest was also behind it. I know that, my grandfather Artur came from Baiersbronn-Obertal, we always celebrated our annual family day there, and in the “Blume” inn at the entrance to the village, Herberger’s heroes have left their mark to this day, the old photos of the innkeeper with Sepp and Fritz keep the glorious past alive. Before the World Cup in Switzerland, the would-be world champions refuelled in Obertal for the miracle, and on the mini-golf course Fritz Walter set a new record: 32 strokes. As a boy, I later tried to break it every year, but surrendered unsuccessfully at some point.

At the World Cup, the Hungarians beat our Germans by eight strokes. Ferenc Puskas and his Puszta Wizards, undefeated in four years, dismantled Fritz Walter’s team in the preliminary round, the final score 8:3. In anticipation of defeat, Herberger had left out his best players as a precaution, and he would have been better off sparing his sensitive captain the humiliation. “For years I was so excited before every game that I felt sick,” Walter once confessed, “I often sat on the toilet until shortly before kick-off.” But Herberger, a fox when it came to people management, found the proven antidote at the “Belvedere”: in room 303 he combined the brooding man with the carefree Helmut (“Boss”) Rahn, a mood cannon. “Helmut,” said the boss, “build me up Fritz.”

The two complemented each other in such a way that the Grübler calmly sank two penalty balls into the Austrian box in the semi-final and the Boss first scored the 2:2 in the final against the unbeatable Hungarians and then also elicited the cry of all cries from Herbert Zimmermann: “From the background Rahn should shoot, Rahn shoots, Tooor, Tooor, Tooor – Tooor!”

As world champion, Fritz Walter received 2300 marks, a motor scooter, a couch set, a television, a hoover and a sewing machine. He wrote the bestseller “3:2” and, to make up for the lost war years, played in the 1958 World Cup in Sweden. And it almost came to the final duel between the kings: 37-year-old Fritz Walter against 17-year-old Pelé.

A terrible semi-final shattered the dream, especially that of the chronicler here, who was eight years old when he attended his first World Cup. A boy forgets nothing. I lay in front of the radio, first shaking and then crying. It was one of those music chests that were very popular at the time, on the left was the compartment with the eggnog and cognac, on the right the record player with the radio, and from it 50,000 Swedes roared their “Heja! Heja!” on that dreadful evening that ended with Herbert Zimmermann relaying to the home front how Fritz Walter was fouled and carried off the pitch by the cotrainers Schön and Gawliczek, his head buried in both hands. For the rest of the game he limped like a war invalid at right wing.

It was Fritz Walter’s last international match. Afterwards, he became an honorary captain, and among other things, a street, a school, a railcar of the Bundesbahn, a champagne, a football tournament, a foundation and the stadium at the Betzenberg were named after him, and in 2002 he was laid to rest. But he lives.

Because a great dead man never dies. In the “Belvedere”, his jersey has been reproduced for decades, and flanking it, on the occasion of a round birthday of the Bernese wonder, there was also an umbrella with the imprint “Fritz-Walter-Wetter” in Germany for 14.90 euros. It was modelled on the umbrella held out to the German captain when FIFA President Jules Rimet presented him with the World Cup trophy in the Wankdorf stadium.

It was a mess on 4 July 1954 – but that’s the way Fritz wanted it.

by admin | Nov 10, 2022 | Oskar Beck EN, World Cup

Olli Kahn has gone into hiding, on holiday in Sardinia, recovering. How does a flawless player cope with a mistake – and then with one like the one he made on Sunday in the World Cup final in Yokohama?

When Oliver Kahn squatted on the ground after the World Cup final and leaned against the goal post with his back extended, looking for support, done with himself, God and the world, it was an advantage that no one handed him a gun – he would have gratefully given himself the bullet.

What was going on inside him?

To have a rough idea, you only need to know what father Rolf once reported from his Olli’s childhood: “When the boy lost at Mensch-ärgere-dich-nicht, the pieces flew around my ears.”

It must have been something like that, only much more terrible, when the best goalkeeper in the world lost the World Cup final in Yokohama last Sunday. Instead of the Olli-annoy-you figures, this time he peppered away his gloves, and for the rest he would have gone mad on the spot if, because it is the incurable professional disease of all goalkeepers, he hadn’t been before. A goalkeeper has to be crazy, otherwise he perishes on the fine line between hero and fool.

Early on in the 1990s, when he was in his early 20s, Kahn explained his job description to me. At that time, he was a promising talent in the goalkeeper’s box at Karlsruher SC and had not yet experienced much, but he already knew perfectly well what kind of professional challenge he had saddled himself with: “As a goalkeeper, you are a lone fighter,” he said, “a field player can clean up his mistakes, but the goalkeeper cannot. Life in goal makes you lonely.” Especially a mistake like that.

It was his only one in the whole World Cup.

What a great, unsurpassable, overwhelming tournament he had played, friend and foe had celebrated and feared him as “King Kahn” or “Titan”. Without the hotshot in goal, Rudi Völler’s DFB team would not have made it to the final, but would have flown home quickly after the preliminary round on sneaky routes, economy, wooden class, and probably been greeted at Frankfurt airport with a hail of tropical fruit and rotten tomatoes. But for three reasons the team ended up in the final instead, namely “with struggle, cramp and Kahn”, as TV reporter Marcel Reif truthfully reported. The best goalkeeper in the world was also voted the best player of the World Cup before kick-off. And then this: he loses this final match, the all-important one, the most important of his career.

“It will torment me for a few days,” he says in the dark night after the mishap.

A few days? All his life it will haunt him, for the world is mean. “The only people who remember you when you come second are your wife and your dog,” said the Briton Damon Hill when he once again couldn’t get past Michael Schumacher in Formula 1. Whereas Kahn is now trying to get rid of the ghosts not with his wife and dog, but with his wife and child. He has allegedly fled to Sardinia, on holiday or in therapy.

At this moment he is probably standing in front of the mirror in his hotel room, berating himself, or biting his cheek, as he occasionally does with opponents in the Bundesliga, with his chin thrust out to the hilt and a grimace of self-contempt. For only a flawless and number one is good enough for someone like Kahn, as it was in his early years at KSC, when rivals Famulla and Wimmer disputed his place in goal – poor Famulla, Rudi Wimmer remembers, never lay down in a room with Kahn in the hotel for safety’s sake, “for fear that he would press the pillow on his face at night.”

Olli’s wife doesn’t have to be afraid of that now, but she has to be prepared for everything else. Does he lash out in his sleep? Does he rattle off Rivaldo’s shot again in his nightmares? Does he talk to himself in a gruelling manner? Does he pound his fists against the bedside drawer? How does Kahn deal with this low point in his career, which he suspects there will be no lower? How does he deal with the pity and the knowledge that he has squandered the myth of invincibility? As he squatted down there in the grass, conquered, defeated and inwardly buried, Sat 1 reporter Werner Hansch said: “He comes closer to me at this moment. He is among us again – as a human being.”

For Kahn, this is no consolation. The alien against the rest of the world, you can get used to such headlines as a goalkeeper. “The stone-faced man is a giant,” a Dallas paper had marvelled at him after the US youngster Landon Donovan froze free in front of Kahn like a rabbit in front of a snake – the scene coincided with the blueprint transferred to real life of that TV commercial in which a penalty taker, seeing Kahn in front of him, turns and flees in mid-attack. So at some point, as a goalkeeper, you become a knight in steel armour against whom everything bounces off, year after year Kahn has become more and more worthy of this image, until last week he hovered completely above everything, “Bild” made it short: “The fist of God.”

At most, the Almighty still lived on the floor above Olli – but he obviously got fed up with the magic and set the celestial hierarchy right again with the shock of Yokohama.

How does the fallen giant now find inner peace again in Sardinia? No one knows, but it at least feels reassuring to hear that he allegedly likes to listen to Vivaldi and Tchaikovsky to relax and, in emergencies, also relies on the book “Mental Strength” by James E. Loehr. So there is much to suggest that Kahn will soon be spitting in his gloves again and that the world’s greatest gunners should start thinking about how best to take cover from him.

The German Chancellor has also intervened in the meantime and declared the return of the national goalkeeper to his old strength a top priority, so to speak. “Olli Kahn is not smaller after this mistake, that’s nonsense,” Gerhard Schröder has reassured the beleaguered nation, and flanking this we have heard a TV prophet on Sat 1 say: “A Kahn is coming back, stronger than ever.”

Even stronger? God help him.

by admin | Nov 9, 2022 | Oskar Beck EN, World Cup

The third goal at Wembley has been avenged: Helmut Haller stole the World Cup ball that wasn’t in the goal in 1966 after the final whistle – and sold it back to the English for a lot of money years later.

Recently, a 16-year-old robbed a liquor shop and forced the handover of high-proof drinks under the threat of force of arms – but the punishment was mild, the judge found extenuating circumstances due to a difficult childhood.

I know what he means.

Because a childhood can’t be more difficult than mine. I was eight at the first World Cup I saw, that was in 1958, and we were shamelessly cheated in the semi-final against the Swedes. But above all, in 1966 there was also that traumatic key experience that a growing 16-year-old normally can’t cope with without becoming delinquent – that unbearable moment on the unspeakable 30 July 1966 when Rudi Michel shook the sentence into his ARD microphone that no German ever forgets: “No goal! No goal! Or is it? And now, what does the referee decide?” Gottfried Dienst, the Swiss whistle, decided: goal.

The German Football Association is opening the exhibition “50 Years of the Wembley Goal” this weekend and will hopefully unveil a memorial so that such an injustice never happens again. But in any case, the English have already received the right damper: The auction house “Sotheby’s” recently wanted to auction the jersey in which Geoff Hurst shot us Germans with three goals in the then World Cup final – but nobody buys it.

A shelf warmer.

Actually, any halfway sophisticated English souvernir hunter would have to sell house and home for a piece of 1966 World Cup breath, but Hurst’s hero shirt, estimated at 600,000, did not even attract the minimum bid. The red piece of fabric with the “10” is shunned as if it had blood on it. Yet it is only Hurst’s sweat and the tears of Hans Tilkowski, Willi Schulz, Siggi Held or Uwe Seeler that will open the DFB exhibition in Dortmund on Sunday. When they hear about Hurst’s shirt flop, the German players will be winking up at Helmut Haller – and our unforgotten rascal from Augsburg will be slapping his thighs with his rascal grin and warbling the old popular song “Souvenirs, Souvenirs” by Bill Ramsey.

For Haller, who crowned the legendary midfield trio Haller-Beckenbauer-Overath at that World Cup, stole the ball after the final whistle.

The brazen theft is documented by pictures: Haller is seen curtsying to the Queen in the box with the ball tucked under his arm. Or later at the closing banquet, when he has the Three Kings of the World Cup sign their autographs on it: Pele, Eusebio and Bobby Charlton. Helmut Haller was a master of investment. He felt that what he had snatched up was the most famous ball in football history – the ball that wasn’t in it.

That brings us back to that bloody, bloody 101st minute. Geoff Hurst shoots, the ball hits the crossbar – and down. Off the line? On the line? Behind the line? Referee Gottfried Dienst, a postal worker from Basel, doesn’t know. His linesman Tofik Bachramov, a mustachioed man from Baku on the Caspian Sea, doesn’t know either, but suddenly yells at Dienst: “Is gol, gol, gol!” 3:2. The goal of the century has been scored, but only one person in the world has really seen it: Heinrich Lübke, our head of state. It’s still just after the war, and in a dissolute mix of German humility, political correctness, and incipient dullness, the German president claims: “The ball was in.”

Even Geoff Hurst is far less sure later (“Goal? Probably not”), and his 4:2 is irregular in any case, because on this last counterattack he has to sprint past English fans who are already celebrating on the pitch. Helmut Haller takes advantage of this chaos to steal the ball with the presence of mind. At home in Augsburg, he gives it to his son Jürgen for his fifth birthday, and he practices so diligently with the round thing in the garden that he later becomes a Bundesliga player. Sometimes Papa Haller also lends out the ball, for example at parties, exhibitions, and company anniversaries. Until, thirty years later, the English scratch their heads: “Where is our World Cup ball anyway?”

“I don’t have it,” Hurst swears. A triple final goalscorer, Sir Geoffrey, knighted by the Queen, suddenly believes himself to be the rightful owner of the ball, and the English revolving press goes to war, launching the great homecoming campaign as part of an emotionally stirred-up campaign. Finally, in April 1996, the time has come. Haller’s son flies to London with the object of desire, and the ball is kissed by Hurst in a flurry of camera flashes after landing. It then lands in a display case at “Waterloo Station”, and well greased it now crowns the National Football Museum in Lancashire.

Did Haller have a heart for Hurst? More credible sounds the thesis that a patriotic English group of investors had paid a ransom of 240,000 marks to the smart Augsburg, whereupon the tabloid “Sun” immediately foamed at the mouth: “That greedy Kraut.” Either way: Helmut Haller was better served with the World Cup ball than Hurst with his jersey. As the inventors of fair play, the English are apparently so fussy that they won’t even give this dodgy shirt a pinch.

For Sir Geoffrey, it’s all rather embarrassing. And “Sotheby’s” looks enviously to Munich, because unlike in London, there were buyers there without any problems the other day when Adolf Hitler’s socks, Eva Braun’s burgundy summer dress, and Hermann Göring’s silk pants were auctioned off.

by admin | Nov 9, 2022 | Oskar Beck EN, World Cup

The match of the century celebrates its anniversary. Football has never been more wonderful and terrible than on 17 June 1970: In the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City, they put the arm in the noose of our maimed emperor, and at home we felt like being roped – the screams of joy from the neighbouring balconies became too unbearable as the night wore on.

A few days ago, the head of the sports desk tested my long-term memory and my aptitude for the following text with the question: “Where were you on 17 June 1970?”

All of us know these historical interrogations. Where were you when Neil Armstrong walked on the moon? Where were you when the Berlin Wall fell? Where were you when the planes flew into the Twin Towers in Manhattan?

Where was I on 17 June 1970?

At home in my television chair, like every dutiful German, I was alternately roaring with happiness and cursing with rage.

It was fifty years ago, but I can still see my father in front of me, clutching his heart in the middle of extra time and saying, “I have to go to bed, I can’t take this.” Then he fled, leaving me alone with this most wonderful and terrible football match the world has ever seen.

You have to be Italian not to have suffered permanent psychological damage that night. We Germans will never come to terms with this World Cup semi-final in Mexico City, which began as football and ended as torture. We are like Gerd Müller, who lay on the grass of the Aztec stadium at the end and swore: “I don’t want to see any more of this game for the rest of my life. I would cry.”

Triumph and tragedy have never come closer than on that night. Emotions rode roller coasters and ghost trains, and the incomprehensible is immortalised at the Azteca Stadium with a commemorative plaque to which football fans have bowed like pilgrims in Mecca for fifty years: “Italia – Alemania. 17 de junio de 1970. Partido del siglo.” The match of the century.

The dramaturgy of horror and horror begins in the seventh minute. 0:1, Boninsegna.

Roberto Boninsegna. No one suspects at that moment that this name will soon haunt us Germans in our sleep. That we would meet him again just one year later, on a sad European Cup night when Günter Netzer played the game of his life. With his Gladbach team, the “King of the Bökelberg” knocks the reigning World Cup winners Inter Milan off their feet 7:1. Only a failure of the floodlights could save the Italians that night, or the throwing of a Coke can. The warehouse worker Manfred K. then actually fires it, at the head of Boninsegna, who is making a throw-in. Others swear that the can only grazed his back. The can was empty in any case, but Boninsegna falls over as if struck by an axe. For seven minutes he lay motionless, the summoning of a priest for the last rites seemed unavoidable, and the dead mouse was finally carried out on a stretcher. The 7:1 score is subsequently annulled at the green table, Gladbach are kicked out, Netzer’s greatest game never took place, and from now on the worst swearword in German football is not actor or rogue, but Boninsegna.

But nobody knows that in the seventh minute on 17 June 1970. All they know is that it is now 1:0 for Italy, Boninsegna’s goal. After that, only Germany is on the attack. Shots, headers, corner kicks, ricochets. Facchetti fouls Beckenbauer. Seeler also falls in the penalty area. “The bastard is cheating us!” curses Müller at some point.

He means Arturo Yamasaki, the Mexican referee. He denies the Germans three penalties and thus provides the template for the smart TV commercial that Olli (“Dittsche”) Dittrich later shoots for a large electronics company. In it, he embodies an Italian Toni as the normal football-minded German imagines him, glittering gold chain, mafia sunglasses, a bucket of gel in his hair and always a cool saying on his lips – in this case Toni laughs at us Germans for always buying new TVs before a World Cup. “What do the Italians buy?” grins Toni. “They buy the referees.”

In any case, Yamasaki becomes the nail in the coffin of numerous German efforts. Although Beckenbauer has only one usable arm left after Facchetti’s foul (the other one has been taped to his body along with his shoulder), the Kaiser drags ball after ball to the front like a war invalid. “A-le-ma-nia!” the Mexicans shout. Overath hits the crossbar, once the ball dances on the goal line, but the bulwark of catenaccio holds.

Then the 90th minute is running and the Italians are counting on everything but Karl-Heinz Schnellinger. “Carlo” they call the man from Cologne, who has been playing for AC Milan for years, as a defender. He never crosses the halfway line there. But suddenly someone from the German bench calls out onto the field: “Carlo, forward!”

“Where to?” Schnellinger is supposed to have shouted back, because he doesn’t know his way around up front – but then he somehow finds his way through, sneaks in front of the Italian goal and instinctively does what he always does at the back: with an outstretched leg he lunges into Grabowski’s cross. 1:1: “Schnellinger, of all people!” shouts Ernst Huberty into his ARD microphone. It is three quarters of one in the night in Germany, and it is the goal for extra time. But above all, it’s the gateway to madness. What happens afterwards sweeps the whole world away. With his pulse pounding, Walter Lutz, editor-in-chief of the Zurich-based “Sport”, wrote how he was overcome by madness “in the most fascinating, stirring and exciting football match I have ever experienced, in the most thrilling and high-class game of this World Cup tournament, in a match in which all the dams burst in extra time, all the floodgates open generously and in which all the basic rules of football are thrown overboard”.

Gerd Müller’s 2:1 unleashes the avalanche of madness. With his thigh (or is it his butt cheek?), he wiggles the ball into the goal, and for the 102,000 eyewitnesses in the Azteca Stadium and the worldwide audience of billions, including me, it is suddenly clear: the Italians are finished, exhausted by the thin Mexican air and the sweltering heat, it is 50 degrees on the pitch. But instead Siggi Held makes the mistake of his life. 2:2 through Burgnich.

By now it’s no longer a game, but a wild mixture of heartbeat, heatstroke and Hitchcock. A “Bild” reporter has himself hooked up to a machine at home in the editorial office that certifies a heartbeat of 139. When Armstrong walked on the moon, he had 120.

2:3 by Gigi Riva.

I sink into my armchair. Every one of us knows moments like this, when he falls away from faith. And the misfortune is not made any more bearable by the staccato of cheers from the neighbouring balconies: “Ita-lia!”

Are the Italians going to finish us off now? No, decides Bomber Müller defiantly. Alongside Brazil’s Pele, he is the star of the World Cup, he has already scored nine goals, and in a rage he now scores his tenth. 3:3. Powerless, Gianni Rivera, the Milan star, stands on the goal line and bites into the net. Then Rivera trots to the kick-off with his head hanging. Italian attack on the left, ball into the penalty area.

3:4 by Rivera.

End. Over. As a decent German, I’m now finished with God and the world, and in the neighbourhood the “Ita-lia!” is getting more and more humiliating. From Wolfsburg we can still hear the VW guest workers celebrating the victory there with honking concerts and the battle cry: “Potato kaput. Spaghetti tastes good.” It’s half past one in the night – and the only nice thing is that 17 June 1970 is over.

by admin | Nov 9, 2022 | Oskar Beck EN, World Cup

“Come on, guys, get a ticket for the final,” said Gotthilf Fischer on July 6th 1974. The next day, the Fischer choirs sang us to World Cup victory, and the Fischer choir reporter had the perfect seat: the German goals fell directly in front of me – but Bernd Hölzenbein fell the best.

There are things you never throw away for the rest of your life. On the evening of the day they became important to you, you put them in the cigar box with the immortal mementos – and dig them out again in quiet moments.

Sometimes it takes thirty years. The dusty souvenir I want to tell you about here today has suffered. The ravages of time have gnawed at it, possibly even a ravenous moth, in any case it is crumpled and appears somewhat torn at the corners. “Munich, 3 p.m., Block E 2, standing room”, it says on the card. And the date.

7 July 1974.

My standing room in Block E 2 was, to put it bluntly, a good seat. It prevented me, for example, from seeing the full impact of the first scene of the 1974 World Cup final – after all, there were about a hundred and thirty metres between me and the spot where Uli Hoeneß left his leg out against Johan Cruyff. Of course, the news of the catastrophe somehow got through quickly to Block E 2: The referee blew his whistle for a penalty, Johan Neeskens scored, the loudspeaker announced the new score, and I let my trunk hang down to my feet in my standing position. But then, at the kick-off circle, which wasn’t all that far away, I saw Müller, who voluntarily wore the unlucky number 13 on his back due to his poorly developed superstition, and with his innate beer calm, the Bomber clapped his hands and shouted that I could almost hear it all the way up in Block E 2: “Let’s go, Uli – 89 minutes to go!”

That was Gerd Müller’s one good deed on that historically valuable day. The other, forty-two minutes later, was his 2:1. After that, we were world champions – and are now celebrating the 30th anniversary, albeit somewhat more subdued than the Miracle of Bern ’54.

That was a different story, from a different time. In 1974, the first millionaires in shorts were already standing on the pitch – no more haggard war returnees balming the sore soul of a flattened nation. Back then, Herberger’s heroes would have carried the goalposts onto the pitch, strewn the lines with sawdust and blown up the ball in order to be allowed to win – they were still other heroes, and their bonuses were still refrigerators, washing machines and gift baskets of food.

To cut a long story short: The Dutch were better on that 7 July 1974 in Munich, but they had no Hölzenbein. It was probably our hook-kicking Hesse who later inspired the poet Salman Rushdie to write the wonderful lines: “Swallows in the penalty area are like a sleight of hand, but good swallows are great art. A good swallow is like a salmon that leaps up, turns and falls back into the water. A good swallow is like the swan dying.”

Bernd Hölzenbein’s against the Dutch was so perfect that, although the rascal lay down right in front of my Block E 2, I wondered for a moment whether it was a swallow at all. Many years later, on the occasion of a DFB anniversary banquet, Schalke’s Olaf Thon was standing in the toilet next to Hölzenbein at the pissing trough and suddenly said, in the middle of the mutual trickle: “Bernd, I think you can give it.” But either way, the main thing was that Paule Breitner’s penalty afterwards was in.

The Dutch, hat’s off, were great. But we had our Seppl again, as in 1954, this time not as coach but in goal, before him Berti drove the great Cruyff to madness and self-sacrifice, and Katsche Schwarzenbeck, the Kaiser’s cleaner, was constantly thrown by Franz Beckenbauer as a rock in the surf of the Dutch attacking waves. But above all, we had our “bomber of the nation”, who was in truth the nation’s dustman – his goals always came out of nowhere.

On 7 July 1974, did even one of us 80,000 in the Olympic Stadium seriously see Müller on the ball before he struck just before half-time? As a surviving eyewitness from Block E 2, I can still describe the incident at first-hand today: Bonhof goes diagonally upright in front of my eyes, drives the ball flat and blindly inside, Müller stops it with his back to goal, hopelessly so, but suddenly he puts his Swabian butt out, turns around his own butt cheek, and the rest he had already sung about on record shortly before: “Then it goes boom…”

As if unleashed, Block E 2 collectively fell into each other’s arms at this moment, and exhausted by the cruel, nerve-racking, second-half onslaught of the Dutch on the goal right in front of us, we sank to our knees at the final whistle like our bomber Müller – unfortunately, he lit a fat cigar at the banquet in the Hilton in the evening, puffed away with Breitnerpaule and declared his resignation.

Apart from that, it was a fantastic day.

If only because of the Fischer choirs, who provided the musical framework for this great match in the Olympic Stadium and whom I still can’t praise enough thirty years later – for it was the case that Gotthilf Fischer had the best idea of his life the day before the match. One Remstalian washes another’s hand, so the great choirmaster said to the little local reporter B., who was still a special reporter for his district newspaper at the time, focusing on Fischer choirs, without further ado: “Come with me, guys, we’ll get you a ticket for the final.

And then also in the corner where the goal was scored by Breitnerpaule and Bomber Müller, and Hölzenbein over the outstretched leg of Wim Janssen. At the fiftieth anniversary at the latest, I’ll get out the dusty ticket again, and the grandchildren will be flabbergasted with awe: “You were there, grandpa?”

You bet I was. Gotthilf even waived the 15 marks.