Rudolf Kreitlein became famous as the “brave little tailor” at the 1966 World Cup. He wanted to send the Argentinean Rattin off the pitch, but he played dumb and simply didn’t go. Out of self-defence, Kreitlein became a revolutionary – and invented the yellow and red card the next day.

As a journalist, you have to prepare yourself conscientiously for the risks of a World Cup. That’s why, before leaving for South Africa, I quickly went to the doctor to get vaccinated against plagues, but also to the Stuttgart theatre to get vaccinated against referees.

“Referee Done” is the name of the play currently running there. Thomas Brussig wrote it, and it’s a wonderful but almost tragicomic and sad play – about poor guys who run back and forth, aren’t allowed to score a goal and don’t get any applause.

On the stage, which has been redecorated into a dressing room, three actors slip into the skin of referee Uwe Fertig and his two linesmen. Shortly before kick-off, they clamour with each other about their inhuman fate of standing out there again as whistles in the rain and being put up against the wall as a black pig, they tear their mouths off about the rogues and swallow kings who shamelessly tricked them, In short, they show us how referees get in the mood before kick-off to be booed, mobbed, abused, shouted at, insulted, threatened and massacred in every conceivable way by 80,000 people.

Why do they do it anyway?

When it comes to the answer, Uwe Fertig slaps his thighs with a nasty look of revenge: “As a clever referee, you can still become immortal – all it takes is one questionable whistle to set the football world on its ear.

Living proof of this punchline of the stage play is encountered almost daily. With astonishing regularity that can no longer be a coincidence, smart referees lead the world’s most famous football stars through the ring like dancing bears on a nose ring in such a way that I spontaneously have to tell the crude joke about the devil here. He asks Peter on the phone if he can imagine a gripping football match between heaven and hell one day in the distant future, whereupon Peter warns him: “I’d love to, but you won’t stand a chance, because all the gods will be playing for us, Pele, Maradona, Beckenbauer…”.

“But we,” the devil interrupts him with a smile, “have the referees.”

In any case, one thing is true: particularly self-confident referees who think something of themselves prove on selected days that they absolutely need a certain sense of power for a fulfilled life, especially in the form of pulling out yellow and red cardboard lids with which they make the highest-paid millionaires stand at attention in short trousers with impunity.

Which finally brings us to the subject: Who invented these cards?

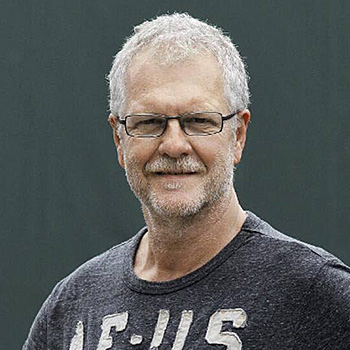

For the answer to that question, you don’t have to go far if you’re coming from Stuttgart’s theatre house at Pragsattel. Down into the city and then up to Degerloch, where the sought-after cult figure lives: Rudolf Kreitlein.

I once curiously rang his doorbell and he let me look into his thick folders, into which he pasted the newspaper articles from the most important day of his life. Until then, he was just a small-time tailor, but with a single whistle he then became world-famous overnight as the “brave little tailor” at the 1966 World Cup. “Even my referee’s outfit was homemade,” Kreitlein told me – and then the story with Rattin.

That was in the quarter-finals. England met Argentina at Wembley, and at some point Antonio Rattin, the captain of the Gauchos, looked down at the German referee from above. Rattin was a giant, and Kreitlein only a running metre, but for all that he was in the driver’s seat. Because the two were unable to clarify the delicate situation verbally, Kreitlein “read from Rattin’s facial expression” that he had insulted him – and “with the gestures of a castle actor”, an eyewitness later noted, the little brave one tried to send the Pampariesen off the field, in the form of flailing movements of the arm and flanked by a drawn index finger. But Rattin would not be scared away. Understand nothing, he hinted, only train station. Only after seven minutes of turmoil did armed London bobbies finally manage to lead the uncomprehending Argentine away.

“We have to find something so that players and spectators understand our decisions better,” Kreitlein said afterwards to English FIFA referee Ken Aston, who had already saved him from the worst during the ruckus on the pitch with full use of his imposing body. Legend has it that Aston had to stop at a traffic light on his way home through London that same evening, and suddenly he had a flash of yellow-red inspiration, and the next day it was clear to Aston and Kreitlein: warning cards were needed. Since then, football has been regulated in the same way as traffic.

As a brave little tailor and pioneering yellow-red pioneer, Kreitlein was invited to Bellevue Palace by the German President last year for his ninetieth birthday, for dinner and the ceremonial acceptance of the Federal Cross of Merit. Normally, only hand-picked Germans enjoy this award, but on rare occasions, a Swabian tinkerer who, with an ingenious invention, has prevented football from perishing from its misunderstandings and turmoil on the pitch also receives it.